Not long ago, I conducted an experiment and told some friends, “I think I’m going to move to Africa.” In saying so, I was met with an uneasy silence that said: “Well, why would you do that?!”

It’s funny, because Africa, with its 54 countries, is not only rich in natural resources, flora & fauna, and cultural heritage, but it is rich in creative capital and innovation, and it is boldly embracing the future.

I recently attended the 2024 Pridelands Wildlife Film Festival (PWFF), now in its 3rd edition, in Nairobi, Kenya. Simply put, the PWFF is a nascent, wildlife conservation film festival by Africans for Africans.

“’Until the lions have their historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.’ A quote by the late Chinua Achebe, a Nigerian novelist, poet, and critic.”

This quote, front and center on the PWFF website, instantly tells us what is unique and compelling about this film festival. This is not just about wildlife conservation, and it is not just about filmmaking and storytelling. This is a platform to foster agency, empowerment, and equity by Africans for Africans (and by extension, to all BIPOCs) in conservation storytelling. To be clear, when I say Africans, I mean those indigenous to Africa. The Pridelands Wildlife Film Festival is unique in its desire to rebalance who gets to tell their wildlife conservation stories in this world, and who gets to be celebrated, awarded, and recognized for doing so.

Founded by young, female, Kenyan filmmaker, Fiona Tande, two of the aims of the Pridelands Wildlife Film Festival are to:

“honor the talent, culture and excellence of African storytellers in the realm of wildlife & conservation; and

to champion the power of African storytellers in altering global narratives about wild Africa, by providing a platform for their emerging and crucial voices in conservation and wildlife filmmaking.”

Films like “Empalikino” (Forgiveness) by Kenyan filmmaker, E.M. Mwangi, and “Kuishi Na Simba” (Living with Lions), last year’s Best Film, by Tanzanian filmmaker, Erica Rugabandana, tell us the story of what it’s like to live with lions from the perspective of local Africans, who must decide how to come to terms with and approach the symbolic and economic losses resulting from the predators. The film, NDossi, by Kristina Obame, which won this year’s Best Short category, is a beautiful, folkloric, lyrical story of the value that soil and the forest play for the Gabonese communities in the Congo Basin. “Soil is their identity, and the forest is their pharmacy. If the forest is lost, so too is their wisdom.”

Indeed, the PWFF is more than just a film festival. It is a platform for Africans to share their own stories of wildlife conservation – which are rarely told and often overlooked – in their own voices, from their own unique perspective. This is an intentional rejection and shedding of external narratives, to make way for authentic stories and perspectives by Africans. The festival is part of a growing movement in Kenya, and beyond in the African continent, of Africans asserting their own voices and agency to rewrite the narratives of Africa and its people.

The PWFF film screenings also included a variety of international conservation films, such as “The Last of the Nightingales” on American renowned soundscape ecologist, Bernie Krause, and his recordings of the sounds of the natural world; as well as the comically educational, “Cactus Hotel”, which narrates daily life at the American desert ecosystem through the perspective of its greatest host, the Cactus.

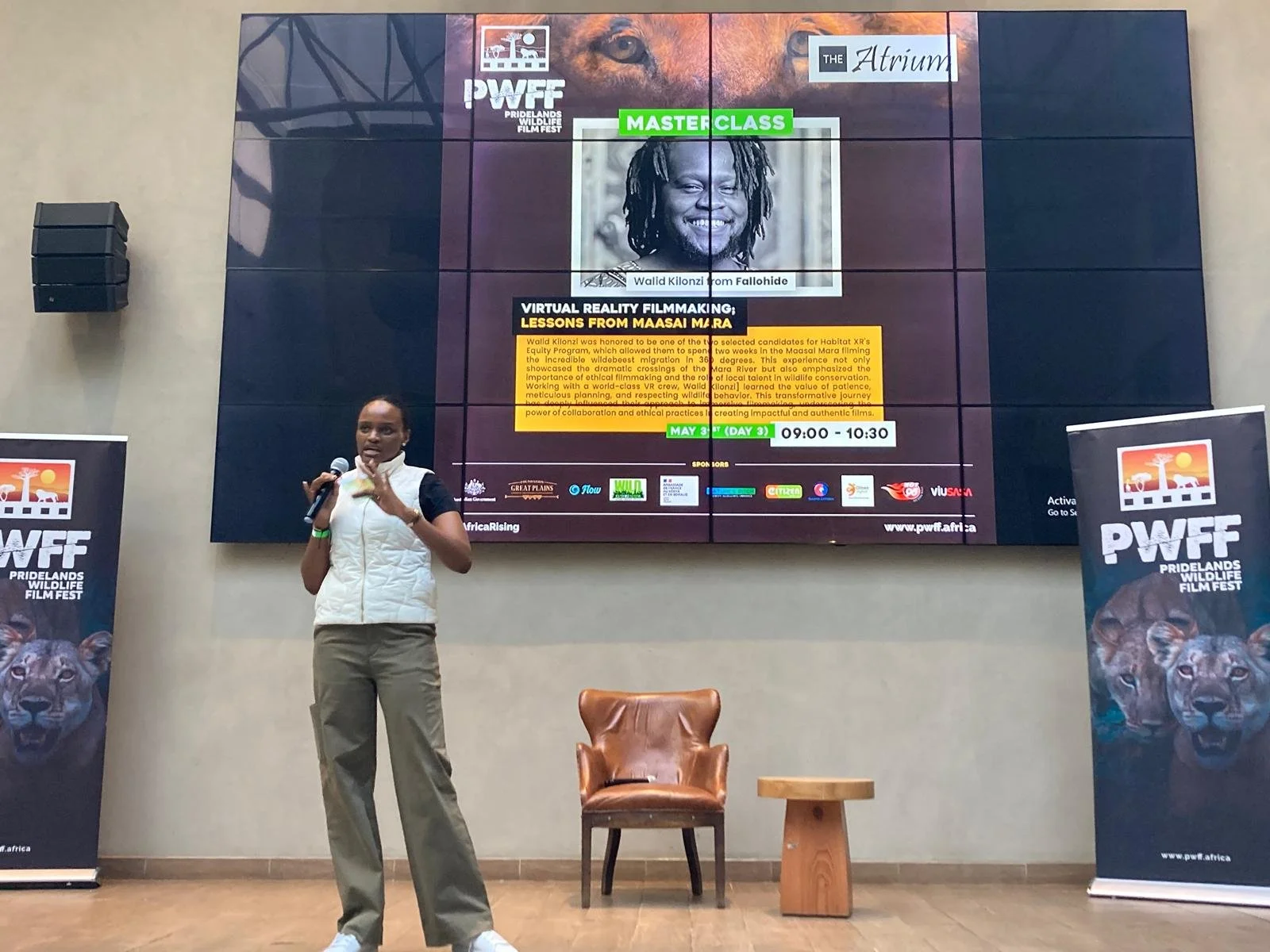

In addition to screenings of African and International documentaries on wildlife conservation, the PWFF offered an interesting array of sessions and panels. A session on Virtual Reality led by Walid Kilonzi of African-based Fallohide, offered an introduction to Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality and Mixed Reality, and showcased how virtual reality filming & technology in Kenya is being used to promote conservation education globally. Another session, led by William Ouma of Expert Drones Africa and Dibblex Soyiantet of the Mara Elephant Project, showcased how drones are being used by African rangers to effectively redirect elephants away from farmers’ crops, thereby preventing dangerous human-wildlife conflict. The rangers have also used these drones to help the local population during Kenya’s recent floods.

Host Marley Sianto introduces Fallohide's Walid Kilonzi.

One of the more controversial sessions in the festival focused on AI in Filmmaking, and AI’s impact and potential in conservation storytelling. A diverse panel of filmmakers (both African and International: Mercy Mutisya, Mike Mwithi, Amos "Guzman" Cheriuyot, Christopher Paektau) discussed how creatives and filmmakers can engage with AI to harness its potential and benefits, and in some ways, to level the economic playing field of production resources. Of course, it’s hard to convince a room full of weary creatives (filmmakers) that AI is only going to eradicate mediocrity and not human creativity. The panel addressed these ever-present fears & concerns about the ramifications of AI for filmmakers, as well as the variety of benefits and opportunities.

Truth be told, I learned more about Virtual Reality, AI, and drones in three days at the PWFF in Nairobi, than I personally have in my professional environment in the US. More importantly, it was refreshing to see People of Color doing their thing: leading the discourse on technology, and innovation; showcasing their talent, creativity, and ingenuity. This is such a rare thing to experience in the United States, and, in particular, in the progressive but racially-stratified Boston. In the “Land of the Free and the home of the Brave”, or (dare I say it) as musician Jill Scott put it: “Not the land of the Free, but the home of the Slave”, Afro-Indigenous competence is, lamentably, either covertly or overtly resented by a governing populace and society that feels threatened by BIPOC displays of autonomy, competence, empowerment, or fulfillment. It is harsh, it is ugly, but it is true. If you are American and are in denial of the latter statement, look no further than the backlash after Reconstruction in the 1800s; the backlash after the Obama Presidency in 2016; and the backlash after the height of the corporate Anti-Racist movement in 2020. The pattern remains the same.

Back to Africa. One of the most stimulating conversations at the PWFF was the Animated Africa: Shattering Stereotypes in Wildlife and Conservation Narratives session. This panel consisted of a distinguished set of African artists & creatives: Hamid Ibrahim (Iwaju); Maimouna Jallow (Tales of the Accidental City); Nana Akosua Hanson (Moongirls); Malenga Mulendema; Manal Omayer; and Mwara Kungu (the Almasi Project). This panel discussed issues of representation of Africa in terms of its wildlife in animations and storytelling. The conversation delved into how and why it is important to remind Africans of their own stories and of Afro-traditional knowledge within animated storytelling. The panelists also discussed the value of harnessing traditional African spirituality to protect the environment. Of course, this conversation would not be complete without addressing Intellectual Property, and how to utilize IP to achieve social, indigenous equity, as an antithesis to the exploitation of resources and stereotypes of Africa. There is a growing dialogue amongst African creatives, executives, and innovators on how to combat negative, damaging stereotypes of Africa, and how to authentically portray the richly, diverse African continent and its people today.

Animated Africa: Shattering Stereotypes in Wildlife and Conservation Narratives Session

For BIPOCs, like myself, that live in the Global North, and, in particular, in the hyper-racialized US, it so refreshing to experience this alternative reality. To see an Africa and Africans that are breaking apart from the usual, foreign-imposed narratives (you know it, of poverty, war, disease, famine, destitution), and doing so with so much finesse, thought, and panache.

Like the hashtag of PWFF (#AfricaRising), Africa is rising. Rising above the damaging stereotypes and exploitation. Bolstered by generations X, Y, and Z, who are hip, artistic, intellectual, innovative, and, above all, cognizant and assertive, Africans are redefining their identity on their own terms.

I love it. In truth, I recognize parts of myself in them. No one better understands the challenge of constantly defying stereotypes and asserting your agency than professionals of color that live and work in the United States. Those of us who, by virtue of our competence and intellect, are unwittingly perpetually, shattering the status quo, the biases, and perceived norms everywhere we go – whether it’s the office, the courtroom, or even the communal dining table at a luxury safari camp. Our presence at the proverbial table catches many by surprise (and ruffles a few feathers), but our seat plays an important role in shifting the dynamics, shattering the assumptions, and redefining perceptions of who belongs at the proverbial table.

In recent days, we've seen protests, predominantly (although not exclusively) by Gen-Zers in Nairobi, extending to other parts of Kenya, standing up in unity to protest a legislative finance bill that the majority of African Kenyans considered to be exorbitant. They organized, assembled, and asserted their voices to reject what they viewed as a move of guaranteed further impoverishment and exploitation. Although they were initially ignored, their multi-day protests succeeded (for now) in quashing the controversial bill. However, the real significance is that they sent a resoundingly clear message – both within Kenya and beyond to global entities like the IMF. This generation of Africans is ready to grab hold of the steering wheel, and redefine their economic futures and narratives on their own terms.

The Pridelands Wildlife Film Festival encapsulates the spirit of asserting agency and empowerment by Africans for Africans; of rewriting the story of Africa and its biodiversity more authentically. This is what sets PWFF uniquely apart, and it is why I look forward to its next iteration.

- Elizabeth Cerda

The opinions expressed in this article are strictly the author's (my own), and do not represent the views, opinions, or beliefs of any individuals, organizations, or entities mentioned herein.